PFAS: Definition and Classification, Sources and Environmental and Health Impact, Detection and Regulatory

Abstract

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) comprise a structurally diverse class of synthetic fluorinated compounds, characterized by their unique physicochemical properties, environmental persistence, and global distribution. Since the 1940s, PFAS have been used across more than 100 industrial sectors and consumer products, including firefighting foams, food packaging, textiles, and electronics. Because many PFAS resist degradation and can move with water and air, they are now widely detected in the environment and in people.1 This article introduces the foundational chemistry of PFAS, explores their classification and environmental impact, and outlines the primary analytical methodologies used for their detection, with a focus on emerging technologies suited for comprehensive monitoring.

Section Overview

At a Glance:

- What PFAS are: Fluorinated organic compounds characterized by exceptionally strong C–F bonds, often termed “forever chemicals.”

- Why they matter: Notable for persistence, mobility, and bioaccumulation; subject to increasing global regulatory scrutiny.

- Where they occur: Commonly detected in water, soil, air, food, and biota.

- How to detect: Two distinct approaches exists, targeted and non-targeted. For targeted methods, chromatographic (LC or GC) methods with triple quadropule mass spectrometry are utilized along with reference standards for quantification. For non-targeted, high resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) are necessary.

Alternative methods include screening or total fluorine (via AOF, EOF, TOF) by combustion ion chromatography.

How PFAS are Defined

The scientific definition of PFAS has evolved over time. Buck et al. (2011) defined PFAS based on the perfluoroalkyl moiety (–CnF2n+1), establishing much of the subclass nomenclature still used in analytical reports.1,2 Subsequent work by the OECD and UNEP demonstrated that this definition excluded several structurally relevant compounds. In response, the OECD released an expanded and more practical definition in 2021 as follows: “PFAS are fluorinated substances that contain at least one fully fluorinated methyl or methylene carbon atom (with no H, Cl, Br, or I attached).” 3,4

This broader scope encompasses numerous small molecules and polymers, aligning scientific classification more closely with regulatory frameworks.

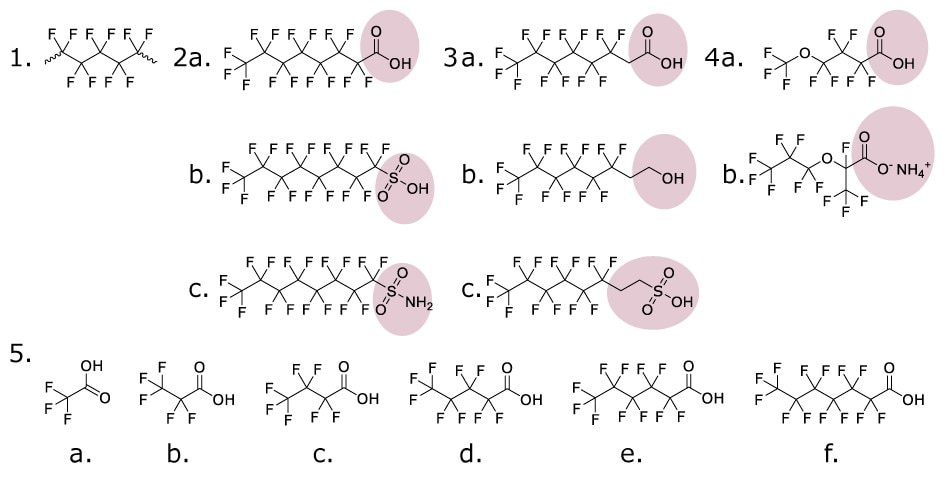

How PFAS are Grouped

Building on the broader definition, PFAS are commonly categorized by laboratories and regulatory agencies into practical groupings that support method selection and data interpretation.

- Non‑polymeric PFAS

- Perfluoroalkyl substances (fully fluorinated tails, e.g., PFCAs, PFSAs)1

- Polyfluoroalkyl substances (partially fluorinated; includes fluorotelomer alcohols/precursors)1 - Polymeric PFAS

- Fluoropolymers (PTFE, PVDF)1

- Side‑chain fluorinated polymers (e.g., fluorinated acrylates)1

PFPEs (fluorinated ether backbones)1 - Chain length conventions (used in methods/regulation)

- “Long‑chain” PFCAs (≥C8) and PFSAs (≥C6)5

- “Short‑chain” are below those thresholds; more mobile, generally less bioaccumulative but widespread6

Figure 1.Representative PFAS chemical structures. Examples of major PFAS subgroups including perfluoroalkanes (1), perfluoroalkyl acids (2a-b), perfluoroalkyl sulfonamides (2c), fluorotelomers (3a-c), perfluoroether acids (4a), cationic PFAS (4b), and short-chain variants (5a-f). Pink highlights show key functional groups.

Why PFAS Persist and Spread

- Persistence: The exceptionally strong carbon–fluorine bonds confer high chemical stability, rendering PFAS resistant to biodegradation, hydrolysis, and photolysis.⁶

- Mobility and transport: Many PFAS exhibit significant water solubility, while certain precursors display volatility; as a result, both aquatic and atmospheric pathways facilitate their long-range transport.⁷,⁸

- Bioaccumulation: Numerous PFAS bind strongly to serum and hepatic proteins,

- Continued release: Ongoing emissions arise from industrial applications, aqueous film-forming foams (AFFF), consumer products, wastewater treatment plant effluents, biosolid applications, landfill leachates, and certain incineration processes.⁷,⁸

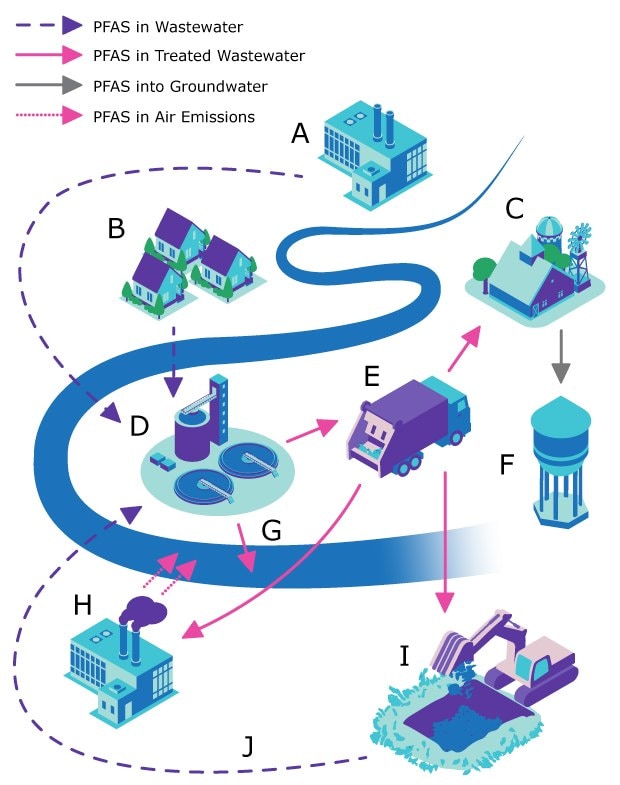

Figure 2.The pathway of PFAS through the environment. PFAS from industrial, residential, and landfill sources (A, B, J) flow into wastewater treatment facilities (D), where incomplete removal allows spread through river discharge (G), agricultural biosolids (C), and landfill disposal (I). Contaminated groundwater eventually reaches drinking water supplies (F), while incineration (H) releases PFAS into the air.

Learn More

Environmental Fate and Bioaccumulation

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) exhibit remarkable resistance to chemical, physical, and biological degradation, a property primarily attributed to the strength of the carbon–fluorine (C–F) bond.1 This extreme stability under thermal and chemical stress has made PFAS attractive for use in industrial applications that require resistance to elevated temperatures, pressures, or corrosive environments. Consequently, PFAS have been widely incorporated into over 200 categories of consumer and industrial products, including surfactants, waterproof fabrics, firefighting foams, textiles and leather treatments, oil-repelling containers, semiconductors, non-stick cookware, food packaging, shampoos, photo films, cleaning agents, and personal protective equipment.4

The broad utility of PFAS has resulted in the commercial circulation of thousands of distinct PFAS compounds globally.4 This widespread use has led to their pervasive release into the environment, with documented presence in multiple environmental matrices such as rivers, groundwater, soils, landfills, vegetation, and wildlife. Their physicochemical characteristics—namely high polarity, thermal stability, and amphiphilicity—enable their persistence and long-range transport in the environment. PFAS have now been detected across all continents, in various environmental compartments, biota, and human populations.

The environmental distribution of PFAS is facilitated by several pathways. Due to their high mobility, PFAS can leach into groundwater, undergo surface run-off into aquatic systems, and disperse through wind-entrained dust particles.1 Atmospheric transport further contributes to their global spread via wet and dry deposition into soils and water bodies.1

While many PFAS are resistant to transformation, certain polyfluorinated compounds—classified as precursors—can undergo partial degradation under environmental conditions, generating terminal degradation products with potentially greater environmental and toxicological impact.3 A prominent example includes the atmospheric oxidation of fluorotelomer alcohols (FTOHs), which yields polyfluorinated aldehydes that subsequently transform into perfluorocarboxylic acids (PFCAs), such as perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA).1 Furthermore, perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) and PFOA may be released directly as impurities from industrial processes or consumer product disposal and can also form through biotic and abiotic degradation or biotransformation of longer-chain PFAS precursors, such as 8:2 FTOH.1

In addition to their environmental persistence, PFAS are amphiphilic and can bioaccumulate in living organisms. Their preferential binding to proteins rather than lipids facilitates accumulation in blood serum, liver, and other tissues. Notably, surveillance efforts initiated in 1999 by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, through the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), have consistently detected PFAS in the blood serum of the general U.S. population. Specifically, compounds such as PFOA, PFOS, and perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS) have been identified in 99% of sampled individuals.9

In summary, the same molecular characteristics that confer utility to PFAS in industrial and commercial applications—namely their resistance to degradation and environmental stability—also underpin their persistence, global dispersion, and bioaccumulation potential, thereby posing substantial ecological and human health concerns.

Sources of PFAS Emissions

The environmental release of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) occurs through both point sources and diffuse sources, contributing to their widespread presence across environmental matrices. Local and regional air emissions can be attributed to industrial activities such as the production of fluoropolymers, construction materials, food packaging, textiles, medical devices, and paints. In addition, professional applications—including the use of aqueous film-forming foams (AFFFs), printing inks, and surface coatings—are also notable contributors.1

Beyond industrial emissions, consumer product usage and disposal represent significant secondary pathways of PFAS release. Items such as cosmetics, personal care products, household textiles, and food storage materials release PFAS during use or upon disposal, introducing these compounds into landfills and wastewater systems.1

A major source of environmental PFAS contamination stems from industrial and municipal wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs). These facilities contribute directly to atmospheric and aquatic PFAS pollution via effluent discharges into surface water bodies. Additionally, PFAS-laden biosolids, sewage sludge, and reclaimed wastewater are often repurposed for agricultural applications, thereby promoting indirect release into soil and subsequent leaching into groundwater systems.4

Other relevant contributors to PFAS emissions include recycling and incineration facilities that process PFAS-containing materials. Under specific operational or environmental conditions, PFAS can volatilize or escape as combustion by-products. Furthermore, landfilling of PFAS-containing waste can result in the leaching of these compounds into underlying soils and adjacent aquifers.

Recent assessments suggest that within the European Union alone, over 100,000 potential emission sites currently exist, with the number projected to increase.2 Considering such extensive and varied emission pathways, PFAS have become pervasive environmental contaminants. Their presence has been documented in multiple exposure routes, including air, drinking water, agricultural produce (e.g., cereals, fruits, and vegetables), dairy products, and other components of the human food chain. The combination of environmental persistence and multi-pathway exposure underscores the growing concern regarding their ecological and public health impacts.

Health and Regulatory Concerns

Long-chain per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), particularly perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), have been extensively studied for their adverse health effects. These compounds have been linked to a range of toxicological outcomes, including developmental toxicity, thyroid dysfunction, immunotoxicity, metabolic disorders, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and increased risk of kidney and testicular cancers.1,5

In response to mounting evidence regarding their persistence, bioaccumulation potential, and toxicity, several regulatory agencies have established health-based guideline values for PFAS in drinking water. These limits aim to mitigate exposure risks in human populations:

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA): Health advisory level of 70 ng/L for the combined concentration of PFOA and PFOS in drinking water.4

- European Union (EU): A parametric value of 100 ng/L for a group of 20 individual PFAS compounds and a broader limit of 500 ng/L for total PFAS, contingent on the availability of a validated method for total PFAS measurement.10

- Health Canada: Maximum acceptable concentrations of 200 ng/L for PFOA and 600 ng/L for PFOS.12

- Australian Department of Health: Drinking water guideline values of 560 ng/L for PFOA and 70 ng/L for the combined concentration of PFOS and perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS).4

These regulatory thresholds reflect growing global consensus on the need to control PFAS exposure through drinking water, although guidance values vary across jurisdictions based on evolving toxicological data and risk assessment methodologies.

How PFAS are Detected

Targeted LC–MS/MS continues to serve as the principal quantitative technique for the determination of named PFAS. Sum parameter approaches (AOF, EOF, TOF) are generally quantified using combustion ion chromatography and are applied as prescreening tools. The TOP assay is employed to oxidize precursor compounds, enabling the estimation of hidden precursor burdens. For suspected/non-targeted PFAS species, high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), is utilized to broaden analytical coverage. Click here for the details on method selection, QA/QC procedures, and contamination control.

Learn More

The accurate detection and quantification of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in environmental matrices is critical due to their widespread occurrence at trace concentrations and the structural diversity among PFAS species. Analytical methodologies must therefore address challenges related to sensitivity, selectivity, matrix interference, and the identification of both known and unknown compounds.

Overview Methods

- Targeted Quantification: LC-MS/MS

Liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) remains the benchmark technique for PFAS analysis. This method provides quantitative data with high sensitivity, often achieving detection limits at the parts-per-trillion (ppt) level. LC-MS/MS is particularly effective for monitoring regulatory compounds when authentic standards are available and the PFAS species of interest are known.5 - Passive Sampling Approaches

In environmental scenarios where PFAS concentrations are extremely low or the sample complexity is high, passive sampling methods are employed to enrich target analytes. These methods enable extended contact times and accumulation of a broad spectrum of PFAS, thereby improving detection sensitivity and analytical reproducibility. Passive sampling is especially useful for standardizing protocols in complex matrices such as sediment, biota, and surface water.6 - Semi-Quantitative Techniques: AOF, EOF, TOP Assay

The complexity of PFAS mixtures, including unidentified precursors, necessitates the use of semi-quantitative techniques. Two widely used methods include:

- Total/Extractable/Adsorbable Organic Fluorine (TOF/EOF/AOF) with Combustion Ion Chromatography (CIC): Sum-parameter methods that estimate the cumulative organofluorine in a sample. EOF isolates organofluorine via solid-phase extraction (SPE), while AOF captures it on granular activated carbon (GAC). In both cases, quantitation is performed by CIC: samples are combusted to convert organofluorine to fluoride, which is measured by ion chromatography (conductivity detection) after prior removal of inorganic fluoride.

- Total Oxidizable Precursors (TOP) Assay: An oxidative method that converts PFAS precursors into terminal perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs)—typically perfluoroalkyl carboxylates (PFCAs) and sometimes sulfonates (PFSAs)—allowing indirect quantification of otherwise undetectable species. The assay is semi-quantitative, and conversion completeness can vary by matrix and precursor chemistry.

These approaches are particularly useful in situations where precursor structures are unknown or analytical standards are unavailable. - Elemental Analysis: Proton-Induced Gamma Emission

Proton-induced gamma emission (PIGE) spectroscopy is a nuclear analytical technique wherein samples are irradiated with low-energy protons. Inelastic collisions with atomic nuclei cause excitation, followed by the emission of gamma rays during de-excitation. Elemental identity and concentration are determined based on the energy and intensity of the emitted gamma rays. This non-destructive method is effective for surface-level detection of total fluorine content. - Structural Elucidation: 19F Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)

Fluorine-19 nuclear magnetic resonance (¹⁹F NMR) spectroscopy provides both qualitative and quantitative information on PFAS species, regardless of the availability of analytical standards. Unlike mass spectrometric methods, ¹⁹F NMR is relatively insensitive to matrix interference, produces clean spectra, and minimizes the need for extensive sample preparation. Advantages include the ability to analyze both known and unknown compounds, high reproducibility, and cost-effectiveness. - Fluorescence-Based Methods and Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs)

Emerging methods for PFAS detection utilize fluorescent and luminescence-based sensors, often enhanced by molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs). MIPs act as synthetic recognition elements designed to selectively bind PFAS compounds, even those lacking electrochemical activity. Fluorometric assays typically measure changes in the signal of fluorophores in solution or immobilized substrates. While these methods offer high specificity, current limitations in sensitivity must be addressed before they can be widely adopted in environmental monitoring. - Electrochemical Sensing Platforms

Electrochemical detection methods are gaining traction due to their low cost, portability, and potential for on-site deployment. Although PFAS are not inherently electroactive, sensors based on redox-active materials can measure changes in electron transfer resistance upon PFAS binding. These sensors are particularly valuable for preliminary screening and prioritization of contaminated samples in field settings, enabling remote assessment of total or specific PFAS burdens.

Standardized Regulatory Methods

The following methods are widely adopted in regulatory and surveillance programs for PFAS monitoring across environmental and food matrices:

- EPA Method 537: EPA Method 537 is a validated U.S. EPA protocol for the determination of 14 PFAS compounds primarily in drinking water using solid-phase extraction (SPE) coupled with reversed-phase liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The method typically uses C18 reversed-phase columns with core-shell particles and metal-free hardware to minimize PFAS loss and background contamination.

- EPA Method 537.1: A U.S. EPA method for detecting 18 PFAS in drinking water using solid-phase extraction (SPE) and reversed-phase C18 LC-MS/MS. It employs low bleed, metal-free columns for strong hydrophobic retention of mid to long-chain PFAS and select short-chain compounds, ensuring trace-level sensitivity and regulatory compliance.

- EPA Method 533: This method targets 25 PFAS, including many short-chain perfluoroalkyl carboxylates and sulfonates plus emerging chemicals, providing improved sensitivity for shorter chains. SPE cleanup precedes LC-MS/MS analysis on reversed-phase C18 columns validated for enhanced retention of both short- and long-chain PFAS. Column choices must accommodate improved selectivity to address early eluting ultra-short chain PFAS, often incorporating columns with delay features to reduce system contamination. Sample volumes typically range from 100 to 500 mL, depending on matrix complexity and detection limits.

- EPA Method 1621: EPA Method 1621 differs from the targeted chromatographic methods, as it measures adsorbable organic fluorine (AOF) in water samples as a bulk parameter, rather than individual PFAS compounds. It employs activated carbon adsorption followed by combustion ion chromatography for fluoride detection, not relying on LC or GC columns for PFAS speciation. Thus, chromatographic column selection is not applicable here; instead, this is a screening method used alongside targeted LC-MS/MS approaches.

- EPA Method 1633: EPA Method 1633 is an advanced, multi-matrix method quantifying 40 PFAS across water, solids, and biota. Its broader analyte list includes legacy PFAS, fluorotelomer sulfonates, perfluoroether acids (PFEAs), and GenX-type replacements. The method demands highly efficient chromatographic separation with longer reversed-phase columns (100–150 mm) packed with sub-3 µm particles or core-shell technology. Mixed-mode or extended column chemistries may be used to resolve complex mixtures and isomers.

- EPA Method 8327: This method is designed for direct LC-MS/MS analysis of 24 PFAS in non-potable water (surface, groundwater, wastewater) without prior SPE cleanup. It uses reversed-phase LC separation, typically on C18 columns optimized for direct injection of filtered and diluted samples. Column and mobile phase optimization focus on matrix tolerance and reliable quantitation despite minimal sample cleanup. The method emphasizes metal-free hardware to minimize adsorption and background contamination.

- FDA Method C-010.02: A targeted LC-MS/MS method developed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for detecting 16 PFAS in foods such as produce, dairy, meats, and seafood, supporting dietary exposure assessments. Discover the articles below for PFAS analysis based on FDA Method C-010.02:

- LC-MS/MS Analysis of 16 PFAS in Salmon

- LC-MS/MS Analysis of 16 PFAS in Milk - FDA Method C-010.03: An updated targeted LC-MS/MS method developed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for quantifying 30 PFAS in a broad range of food and feed matrices, expanding analyte coverage and supporting comprehensive dietary exposure assessments.

- EU Drinking Water Directive (DWD, 2020/2184): Sets drinking water limits for a subset of PFAS, and though it does not specify analytical columns, it endorses methods consistent with EPA standards that typically use low-bleed C18 or phenyl-hexyl stationary phases for trace-level detection.

- Australian National Environment Management Plan (NEMP): Recommends national PFAS monitoring using SPE-LC-MS/MS aligned with EPA methods. Column choices favor robust, low-bleed reversed-phase C18 or mixed-mode columns to cover diverse PFAS species, ensuring regulatory compliance.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Are PFAS “forever chemicals”?

Many PFAS are persistent and resist typical environmental breakdown processes.12 - What does AOF/EOF/TOF measure?

These sum parameters quantify total organofluorine content for screening purposes, not individual compound identities; targeted LC–MS/MS should follow for compound-specific identification.13 - When to use TOP?

The TOP assay is applied when PFAS precursors are suspected and should be interpreted semi-quantitatively, considering the limitations of oxidation efficiency.13

Discover More

- How to Analyze PFAS: Methods, QA/QC, contamination control

- PFAS Column & Solvent Guidance

- PFAS Sample Prep by Matrix

Explore our complete PFAS portfolio to streamline method development, meet evolving regulatory requirements, and achieve confident trace-level detection across complex matrices. Browse products, download application resources, and find the right solutions for your workflow today at SigmaAldrich.com/PFAS.

References

To continue reading please sign in or create an account.

Don't Have An Account?