The Impact of Sample Filtration on Key HPLC Chromatographic Parameters

Sample and mobile phase filtration can significantly impact data quality in high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and other analytical methods. We analyzed the effects of sample filtration as well as filter material and manufacturer on key HPLC parameters including peak height, peak shape and symmetry, retention time, and tailing factor. Results showed that omitting filtration led to significant changes in all tested parameters. Further, data quality varied based on both filter material and supplier. This study highlights the importance of sample filtration and filter selection in obtaining high-quality chromatography data.

Recommended Products

Millex® Syringe Filters for HPLC Sample Filtration

Millipore® Membrane Filters & Filter Holders for Mobile Phase/Solvent Filtration

Evaluating the Impact of Filtration on HPLC Data Quality

In a previous study, both mobile phase and sample filtration to clear particles were shown to maintain high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) column backpressure and thus preserve column lifetime. In this study, the impact of filtration sample preparation on resulting chromatographic quality was investigated through key parameters such as peak height, shape, retention time, asymmetry and tailing factor. Further, the impact of using syringe filters of different materials and from different manufacturers (all with the same pore size rating) on these qualities was also assessed. Chromatograms demonstrated relatively dramatic shifts in retention, peak height, area and even shape when particles were present in the sample versus those that were filtered. Further, filters that allowed even as little as 13% particles to pass through them demonstrated similar negative impacts to data quality. Even the same filter material from two different manufacturers showed slight differences in chromatographic quality, indicating that not all syringe filters perform the same when it comes to chromatography sample preparation. Overall, efficient syringe filtration of samples is one key factor to consider not only to ensure adequate HPLC column lifetime, but also to collect the highest quality data.

Key takeaways from the study are:

- Particulates can impact data quality and possibly cause instrument damage

- Not all syringe filters are created equal

- Filtration of the mobile phase and the sample contribute to the best data quality

Sample and Mobile Phase Preparation for HPLC

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) is a key analytical technique that is used in diverse fields such as pharmaceuticals, environmental analysis, forensics, and food science due to its unparalleled ability to separate, identify, and quantify components in complex mixtures with high precision and accuracy.1 Filtration of samples using a syringe filter (Figure 1A) and mobile phases using a disc membrane (Figure 1B) are common preparation steps in HPLC analysis.2 The overall goal of filtration sample preparation is to remove particles that could potentially clog the HPLC column, leading to high instrument backpressure, reduction of column lifetime, increased signal-to-noise ratio, reduced sensitivity of analysis, and uncertainty in data interpretation.3,4,5

Figure 1.Syringe filters for sample filtration (A) and disc membranes for mobile phase filtration (B).

In this study, the effect of sample filtration on key chromatographic parameters was investigated.

- Retention time (tR)6 represents the duration an analyte spends in the stationary phase. It is crucial for accurate compound identification7 and setting peak integration time windows for quantitation purposes.8 Therefore reproducibility is important.

- The area under a peak (peak area, A) is proportional to the concentration of the analyte it represents and is used to quantify that analyte.9 Ensuring the reproducibility of peak areas from one run to the next ensures that the calculated and reported concentrations are accurate.

- The ideal peak shape is Gaussian – symmetrical and sharp. This makes it easier to integrate compared to asymmetrical peaks, resulting in better sensitivity and higher peak capacity.10 An ideal Gaussian peak shape, however, is rarely achieved in the lab, so there are measurements that are used to indicate good (and bad) peak shape. Asymmetry (AS),11 Equation 1, is a measure of how far from a perfect Gaussian shape a peak may be and can be calculated a variety of different ways, including the calculation of USP tailing factor (tF),11 Equation 2.

Equation 1:

AS = B/A

Where B = back retention at 10% peak height and A = front retention at 10% peak height

If AS > 1.0, peak is tailing

If AS < 1.0, peak is fronting

Equation 2:

tF = W0.05/2f

Where W0.05 = peak width at 5% peak height and f = front width of the peak

If tF > 1.0, peak is tailing

If tF < 1.0, peak is fronting

- Lastly, resolution is a measure of the degree of separation of two adjacent peaks.12 Good chromatographic methods must have sufficient baselines between peaks to separate analytes of interest, calculate key chromatographic factors, and ensure reliable analyses.

Mobile phase filtration using a vacuum setup is a common practice that was shown previously to reduce the introduction of particles into the HPLC system and help keep column backpressure stabilized.13 While sample filtration using syringe filters is a common practice in the analytical lab, there have been fewer studies investigating the impact of filtering samples on HPLC column lifetime and resulting data quality.13

Thus, the goal of this study was to determine the impact of sample filtration on the robustness and accuracy of HPLC analyses, and to provide insights into best practices for sample preparation in analytical chemistry applications.

Experimental Conditions for HPLC Analysis

The syringe filters examined in this study and their properties are listed in Table 1. Hydrophilic PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene) is a high-quality syringe filter material often used for chromatography sample preparation due to its wide chemical and temperature compatibility, relatively low protein binding, and low chemical extractables. Regenerated cellulose (RC) is another common material with similar properties.

Part 1: Filter Retention

In order to correlate particle clearance with changes in HPLC data quality, retention of 0.513 µm fluorescent beads (Bangs Laboratories, Fishers, IN; Prod. No. FSDG003) was determined by filtering 3 mL of a 0.05% w/v bead solution through each syringe filter with a 5 mL syringe barrel. Linearity of the 6-point standard curve was achieved when the samples were diluted 100-fold; thus, filtrate was collected, diluted 100-fold as it was loaded into the plate, and then read at Ex/Em 480/520. Data (mean ± standard deviation, n=3 replicates) was converted into percent bead retention. Signal was tested with both fluorescence and absorbance (undiluted, at 600 nm). Both methods produced nearly the same results after processing (absorbance data not shown).

Part 2: HPLC Study

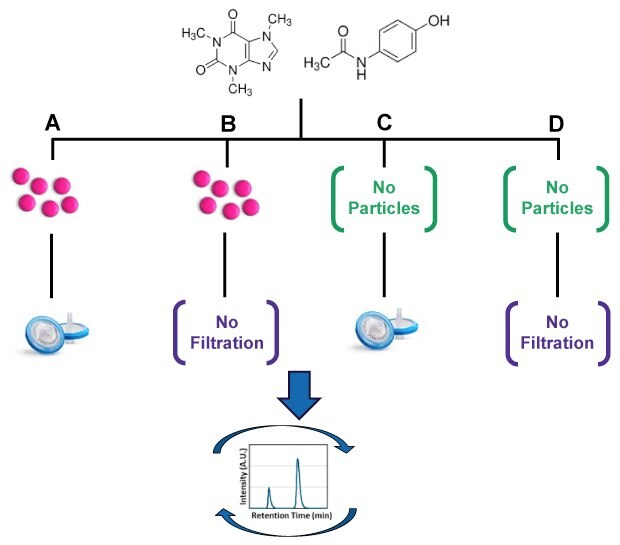

A schematic of the experimental workflow for Part 2 is shown in Figure 2A-D and the HPLC conditions are shown in Table 2. Prior to testing, method development studies were performed to show that the fluorescent beads from Part 1 did not interfere with chromatographic peaks and analyses.

The sample mixture to be filtered was 0.05% w/v beads of 0.513 µm diameter (as described in Part 1), spiked with a mixture of 0.1 mg/mL each of USP-grade caffeine (Prod. No. PHR1009-1G) and USP-grade acetaminophen (Prod. No. PHR1005-1G) in mobile phase (80:20 Milli-Q® water : LC-MS grade methanol, each with 0.1% v/v formic acid; Table 2). Caffeine and acetaminophen are simple, common small molecule drugs that can be easily resolved by an isocratic HPLC method, thus allowing an investigation of peak parameters without the variability that can come with gradient methods.

The caffeine-acetaminophen-bead mixture was then filtered (Figure 2A) using replicates from two lots each of 0.45 µm pore size syringe filters from three different manufacturers (Table 1). The filtered mixtures were compared with an unfiltered case (Figure 2B). Additionally, filtered (Figure 2C) and unfiltered (Figure 2D) drug mixtures with no beads were included as negative controls. During sample preparation, a portion of each filtered and unfiltered sample was drawn directly from the HPLC vial, diluted, and filter retention was measured to ensure that the percent retention of the actual injected samples was consistent with the results from Part 1.

Repeated 10 μL injections were made up to 500 injections or until a set pressure cutoff of >8000 psi was exceeded. After data collection, peak height (H), retention time (tR), peak area (A), asymmetry (AS) and USP tailing factor (tF) were determined from chromatograms constructed at 275 nm and diode array.

Figure 2.Schematic of the experimental setup and procedures. Drug mixtures were exposed to four conditions: 0.05% w/v beads both filtered with 0.45 µm syringe filters (A) and unfiltered (B) , as well as control solutions without beads both filtered (C) and unfiltered (D). Data quality was assessed after repeated HPLC injections. Separate runs were implemented for Millex® syringe filters as well as syringe filters from MFR-1, MFR-2, and an unfiltered case. A fresh column was used for each run after thorough system cleaning and column equilibration steps.

A fresh column (Ascentis® Express C18 2.7 µm, 5 cm x 2.1 mm, Prod. No. 53822-U) was used for each 0.45 μm syringe filter tested (Table 1) as well as in the unfiltered case. Tubing, injector needle, seals, and the HPLC system were extensively cleaned between each test at 1 mL/min or higher without a column installed to ensure all particulates from the prior run were cleared from the system. New columns were installed and flushed with mobile phase at 1 mL/min for at least 10 minutes until column backpressure stabilized, and then equilibrated at the experimental flow rate (0.75 mL/min) until a stable backpressure baseline (ΔP ≤ 20 psi) was established, approximately 10-15 minutes.

Effects of Filter Material and Manufacturer on HPLC Backpressure and Data Quality

There is a correlation between filter particle retention and changes in HPLC backpressure.

Our previous study demonstrated that syringe filters with the same pore size rating can have different particle retention efficiency.5 If syringe filters that do not efficiently remove particles are used to filter samples prior to HPLC analysis, the particles that pass through could end up in the column frit and/or the column itself. Particles that accumulate in the column can affect column lifetime, leading to fewer allowable injections and shorter column life. Though different beads and syringe filters were used in this study, similar results were observed. This was also observed here, where both PTFE syringe filters tested retained >98% particles, which led to successful 10 µL repeated injections up to 500 without appreciable changes in backpressure. Additionally, the RC syringe filter from MFR-2 demonstrated a lower retention (>87%) indicating that approximately 13% of the particles (or a difference of 11% more particles as compared to the PTFE filters) were passing through the filter and into the HPLC vial to be injected. In this case, pressure increased with injection number until the cutoff was reached at 250 injections, and continued to increase until 319 injections where the run was stopped. In the unfiltered case, only 42 injections were made before the cutoff was reached, and pressure increased until the run was stopped at 55 injections.

Data from unfiltered samples were different than data from filtered samples.

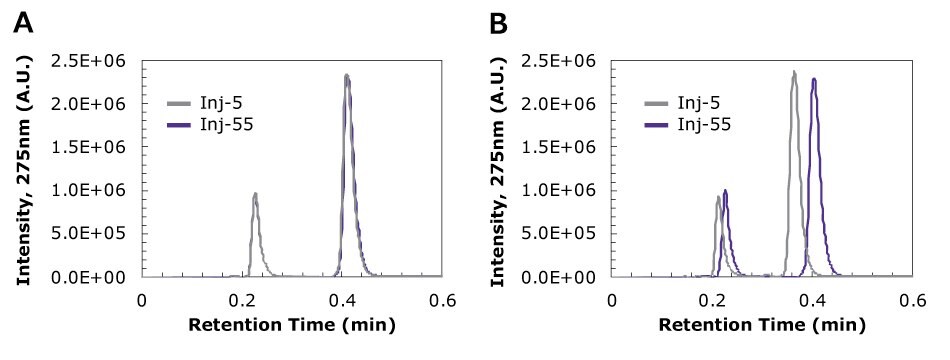

Figure 3 shows the chromatograms of (A) filtered and (B) unfiltered samples of the drug mixture containing 0.513 µm beads (0.05% wt) at injection numbers 5 and 55. Table 3 summarizes the changes in chromatographic parameters between the samples at the same injection numbers. While the trends were similar for both tested PTFE syringe filters, the hydrophilic PTFE Millex® syringe filter is displayed as the representative data.

Figure 3.Chromatograms at 275 nm of (A) filtered and (B) unfiltered drug mixture continuing 0.513 µm beads (0.05% wt) at injections 5 and 55, the latter where the unfiltered sample had surpassed the pressure cutoff. The representative filtered sample depicted used the Millex® syringe filter with hydrophilic PTFE, 0.45 µm pore size, but both PTFE syringe filters tested displayed the same trend at the same injection numbers.

Peak Height and Retention

From the chromatograms, it is clear that if particles are in the system, there is a shift in the retention time and peak height. For both drugs, the retention time decreased due to the presence of particles in the sample (by 0.013 min for acetaminophen and 0.040 min for caffeine). However, in the case of the filtered samples, retention and peak height remained unchanged. While these appear to be small shifts, it is important to note each injection was only 10 µL.

Peak Area

In the presence of particles, the peak area became smaller with each injection (approximately 2-8% decrease in the original size of the peak), while the change in peak area was negligible from injection 5 to 55 for the filtered case. This could indicate a change in the detector sensitivity and signal-to-noise ratio as particles were introduced and backpressure continued to rise.

Resolution

In this study, the two peaks were sufficiently resolved in all cases so any impact of not filtering the sample is not apparent. However, the baseline between peaks became less steady in the case of unfiltered samples, especially when looking at data from the diode array (data not shown). Resolution may be worsened when particles are present for those experiments where peaks are close together or where gradients are used.

Peak Shape and Asymmetry

Calculation of asymmetry and USP tailing factor demonstrated that all the chromatographic peaks from the filtered and unfiltered cases were tailing peaks, showing values between 1.57-2.27 for acetaminophen and 1.42-2.00 for caffeine. In most cases, the filtered cases showed a decrease in AS and tF as injection number increased, indicating that the peaks maintained good quality throughout the runs. However, in the case of unfiltered samples, AS and tF increased with injection number, indicating worsening quality of the peaks as particles were introduced.

Choosing the right filter for chromatography sample preparation is critical to ensuring data quality.

Syringe filters come in many pore sizes, device diameters and membrane materials. Because of the different manufacturing methods, the varied nature of porous materials, and the way to measure their properties, membrane filters from different manufacturers with the same pore size rating can exhibit varied particle retention efficiency5, consequently leading to distinct impacts on chromatographic performance.

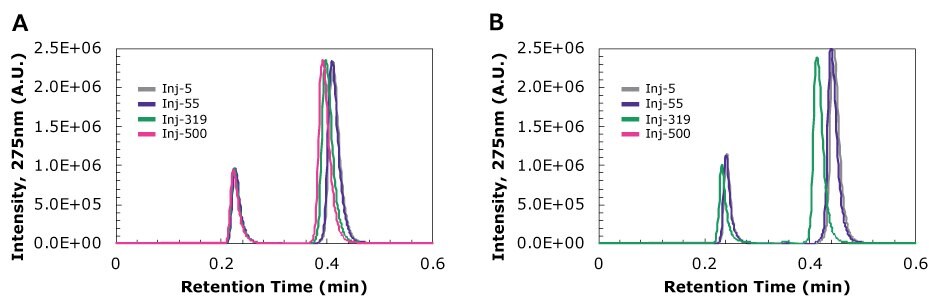

Figure 4 compares the chromatograms of drug mixture containing 0.513 µm beads (0.05% wt) filtered using (A) Millex® PTFE and (B) RC from MFR-2 at injection numbers 5, 55, 319, and 500. A few key observations can be gleaned from these data. First, the data resulting from processing samples with a highly retentive (>98%) syringe filter (PTFE, Figure 4A) showed fewer shifts in retention and peak height with increasing injection number than those from a lower retentive (>87%) filter (RC, Figure 4B). With Millex® PTFE, the earlier-eluting acetaminophen peak is highly consistent from injection 5 to 500 in shape, height and retention while all these parameters appear to shift when particles are introduced. Further, the backpressure increased so much for samples processed with RC syringe filters that 500 injections could not be reached, and by injection 319 (after the cutoff was exceeded and when the run was stopped), peaks for both drugs shifted in a similar way as was shown for the entirely unfiltered case (Figure 3B versus Figure 4B). This means that even as few as 13% more particles going through the filter can cause significant changes in the resulting data.

Figure 4.Chromatograms at 275 nm of drug mixture containing 0.513 µm beads (0.05% wt) at injections 5, 55, 319, and 500 filtered using (A) Millex® 0.45 µm PTFE syringe filter and (B) 0.45 µm RC syringe filter from MFR-2, both with a 0.45 µm pore size rating. Note that for RC, the cutoff was reached and therefore a chromatogram at injection 500 was not collected.

Not all filter materials are created equal.

While examining chromatographic parameters displayed in Table 4, not only were different filter materials and their retentions considered (PTFE vs. RC), but also were different manufacturers considered (Millex® syringe filters and syringe filters from MFR-1 and MFR-2).

Retention Time

While retention clearly shifted in the presence of particles (in the case of RC) and there was a larger difference observed for the later-eluting caffeine peak versus acetaminophen, differences in retention and peak height were also observed between the two PTFE syringe filters. For example, the Millex® PTFE retention times shifted from injection 5 to 500 by 0.226 to 0.223 min (-0.003 min) and 0.411 to 0.392 min (-0.019 min) for acetaminophen and caffeine respectively, while PTFE from MFR-1 showed larger shifts, from 0.221 to 0.216 min (-0.005 min) and 0.393 to 0.363 min (-0.030 min) for acetaminophen and caffeine, respectively. At the same time, the peak heights for either drug were similar for both PTFE filters.

Peak Area

The absolute values for peak area are recorded in Table 4. Overall, it appeared that for all the syringe filter cases, peak area decreased with injection number. Thus, these values were normalized and compared for each peak (Figure 5). For both acetaminophen (Figure 5A) and caffeine (Figure 5B), the decrease became clearer when plotted. The unfiltered case and the low retention RC syringe filter both demonstrated a steep slope of area versus injection number. However, it was surprising to see that even the two PTFE syringe filters had differences in the slope of peak area versus injection number, with the Millex® PTFE having the smallest overall change from 5 to 500 injections. This may be due to subtle differences in retention undetected by the retention assay, leading to more particles passing through into the system in one filter case versus the other, or changes in signal-to-noise ratio due to chemical contaminants in the filters, and strongly implies that even syringe filters of the same material may not perform equally when it comes to HPLC sample preparation.

Figure 5.The change in peak area (calculated using Waters™ MassLynx 4.2 software) versus injection number for acetaminophen (A) and caffeine (B) for the unfiltered case versus RC from MFR-2, PTFE from MFR-1, and PTFE Millex® syringe filter.

Resolution

In this study, the two peaks were sufficiently resolved in all cases so any impact of using different syringe filters for sample preparation is not apparent. Resolution may be worsened when particles are present for those experiments where peaks are close together or where gradients are used.

Peak Shape and Asymmetry

Calculation of asymmetry and USP tailing factor demonstrated that all the chromatographic peaks from PTFE (Millex® PTFE and MFR-1 PTFE) and MFR-2 RC were tailing peaks, displaying values spanning 1.68-2.18 for acetaminophen and 1.50-2.15 for caffeine. In general, both AS and tF increased with injection number, with more significant changes being observed for tF overall. The largest changes were observed for RC between injections 5 and 319 (1.68 to 1.82) for acetaminophen and Millex® PTFE between injections 5 and 500 (1.50 to 1.63) for caffeine despite observed changes in height, retention time and area. This indicates that the presence of particles may not significantly impact degree of tailing unless a threshold amount of particles are present, or more difficult-to-resolve peaks and complex gradient methods are implemented.

Filter Selection for Sample Preparation

In previous studies, both sample and mobile phase filtration proved to be critical to protecting HPLC columns and instruments; however, few studies have closely examined the impact of sample filtration on chromatographic data quality. Here the impact of filtering the samples on chromatographic parameters, including retention time, peak height, peak area, asymmetry and tailing factor, was investigated in detail. Overall, unfiltered samples showed drastic changes in chromatographic parameters by injection 55, even with 10 µL injections. Further, data quality was different when preparing samples using different syringe filter materials (highly retentive PTFE versus low retention RC), showing that even 87% percent retention was low enough to negatively impact data quality. Lastly, PTFE from two different manufacturers had varied data quality, indicating that not all syringe filters will perform the same. Together, these results indicate that for ensuring the best chromatographic data quality, not only is filtration of samples a critical step, but also is careful consideration of filter choice for sample preparation.

References

如要继续阅读,请登录或创建帐户。

暂无帐户?